Chondrichthyans are a group of jawed fish whose skeleton is primarily composed of cartilage and whose teeth and scales are made of dentin (the latter specifically called denticles). Chondrichthyans are divided into two major groups: the Elasmobranchii which includes the sharks, rays, skates, and sawfish, and the Holocephali which includes the chimeras, the only representatives living today and their closest relatives from the geologic past. Chondrichthyan species have a wide variety of feeding strategies including filter-feeding, shell-cracking, and microcarnivory, and many are generalists. Chondrichthyans range in size from a few centimeters to over several meters. They swim in shallow to deep marine open ocean habitats and are frequent visitors to coral reefs where they prey on reef fishes.

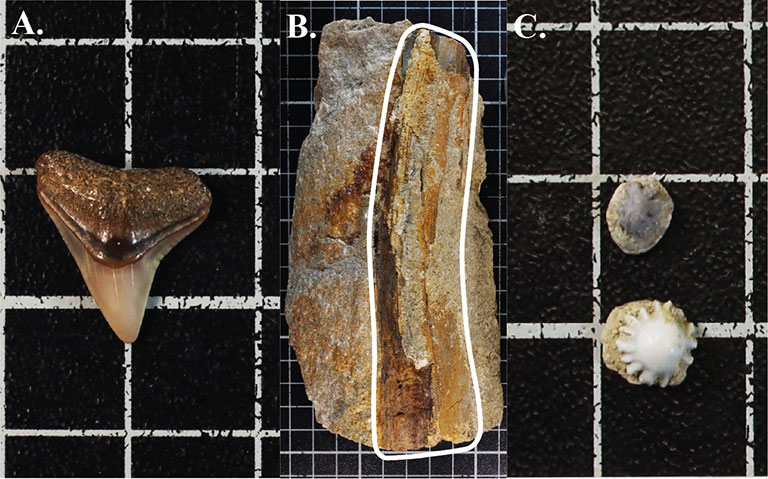

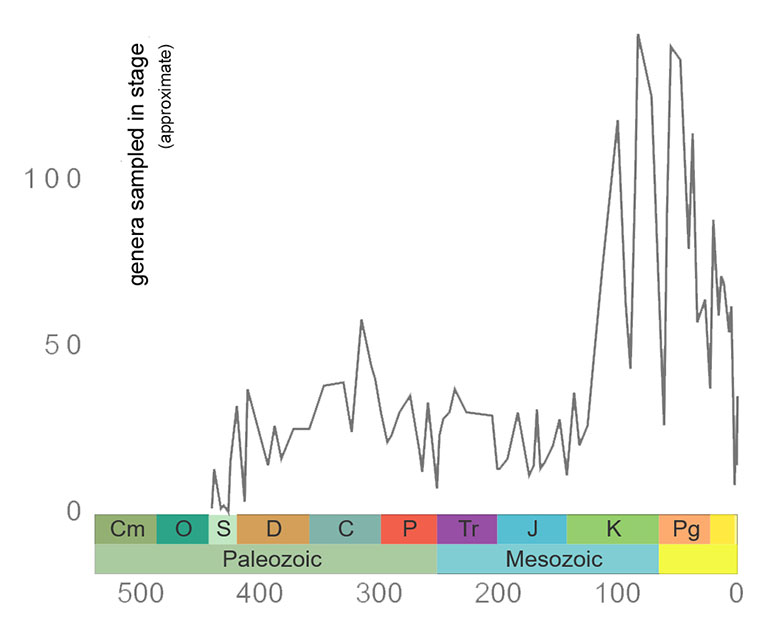

Because cartilage does not preserve well, the much harder teeth, spines, and denticles of sharks are typically the parts found in the fossil record. Sharks and their relatives possibly originated in the Late Ordovician period based on the presence of fossil scales. By the Devonian period, jawed fishes, including cartilaginous fish became more common, but the cartilaginous fish were mostly generalists and not very diverse. In contrast, another group of jawed fishes from this time, the placoderms, were much more diverse and were believed to have possibly limited cartilaginous fish diversity. After the Late Devonian Mass Extinction and the extinction of the placoderms, cartilaginous fish experienced the “Golden Age of Sharks” when they diversified into many species of different shapes and sizes and occupied new roles in ecosystems, including venturing into freshwater ecosystems. Throughout the Permian period, chondrichthyan biodiversity remained relatively stable until the mass extinction event that marked the end of the Paleozoic. Known as the Great Dying, this global extinction hit marine ecosystems especially hard, including chondrichthyans, with 94% of all marine species being wiped out. Fortunately, as seen on the graph below, surviving chondrichthyans were able to radiate back to previous levels.